| | |

|

The Tikhvin Mother of God

Circa 1660

Egg tempera, gold leaf on wood panel

35” x 25”

James and Tatiana Jackson Collection

According to tradition, the original Tikhvin icon was painted by the Evangelist Luke and sent by him to Antioch. From Antioch, the icon was sent to Jerusalem, and later, in the 5th century, to Constantinople where a temple was built especially for the icon in the Blachere district. Although the icon disappeared from Constantinople several times, the last time it left the ancient city was in 1383. The icon first appeared in the Novgorod region of Russia during the reign of Prince Dimitry Ivanovich Donskoy. The first people to record its miraculous appearance were fishermen on Lake Lodoga, who reported seeing a bright light above them. The icon then came to rest about 25 miles from the lake at Smolnovo. The residents there built a chapel and many were cured of ailments. The icon is said to have mysteriously moved about from place to place and in each place, the people erected chapels and soon temples. The icon finally came to rest at Tikhvin, on the Tikhvin River in 1510. A wooden temple was built, dedicated to the feast of the Dormition, and the many who came to venerate the icon were cured of their ailments. The icon is especially revered for helping cure children’s illnesses and protecting families. Several times the wooden temple that housed the miraculous image was leveled by fire, but the icon remained unharmed. Through the efforts of Prince Basil Ivanovich (1503-1533), a stone church was built to replace the wooden temple, which had burned down. During construction, a section of arches crumbled, burying 20 workmen. Although all considered them dead, after three days the 20 men were found alive. About 50 years later, a monastery was established at the church. The Tikhvin Monastery was believed saved from destruction by the intercession of the Tikhvin Mother of God in 1613 when the Swedish forces invaded the country and besieged the cloister. The size of this icon suggests that it was most likely a church icon placed in the local tier of the iconostasis. It is quite probable that the church or chapel which once held this icon was named Tikhvin. The style and color conform in almost every way to the “old” style of icon painting. It is a fine example of an icon which displays a small but all-important feature revealing one of the first elements of Western influence to be detected in traditional icon painting of the period. In this icon the eyes of Mary display an anatomically correct feature which would have never been included in an icon painted only a few decades earlier: tear ducts.

|

|

The Apostle Simon

Circa 1660

Egg tempera on wood panel

44.25” x 21”

James and Tatiana Jackson Collection

This icon is typical of many examples known to have been produced in the Kostroma/Pereslavl-Zalesky region near Moscow. Here the Apostle is depicted facing inward towards Christ, so we know that this icon was from the left side of the Deisis row of an iconostasis. The fact that the borders are not raised would indicate it was held in an iconostasis with deeply carved receptacle-type framing. While the basic composition conforms to the traditional “old” style of icon painting, there are subtle details, such as tear ducts, and calligraphy style, which place it in the post-Nikon category. The scroll signifies Simon is a teacher of the church. The abbreviated inscription in Old Church Slavonic reads, “The Apostle Simon.”

|

|

The Vladimir Mother of God

Circa 1680

Egg tempera on wood panel

12” x 10”

James and Tatiana Jackson Collection

The Vladimir Mother of God is a classic “Tenderness” type icon, so called because the heads of Mary and the Christ child incline in a “tender” cheek-to-cheek embrace. This is the most famous of the icons attributed to St. Luke. It was brought to Kiev from Constantinople in 1155, then taken by the great Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, during his sacking of Kiev. In 1161, it was placed in the city of Vladimir, from which the name is derived. The Vladimir is said to have saved Moscow from Tamerlane in 1395, and from the Poles in 1612. It is considered a great miracle worker, and consequently multitudes of copies exist. The original icon has been repainted several times and after restoration, only the faces of the Mother and Child remain original. The original icon is displayed at the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow. A bitter battle persists between the Russian Orthodox church and the government of Russia over this and many other famous icons. The Church demands the return of icons which were stripped from the churches during the Communist period. The government insists that they are national ethnographic art treasures belonging to the people. This icon illustrates a more naturalistic rendering, a major deviation from the flat old or Byzantine style icons. Here, both the face of Mary and Christ are rounded and somewhat more three-dimensional. The double raised border or kovcheg (Russian) was common in the 17th century, then gave way to flat painting surfaces. The two large inscriptions on either side of Mary’s head are the Greek abbreviated title for Mary, Meter Theotokos or “Mother of God.” The small inscription to the side of Christ’s head, C XC, is the Russian abbreviated form of the name Isus Khristos - Jesus Christ.

|

|

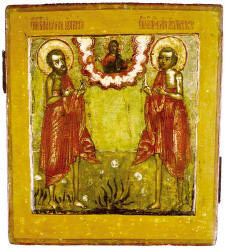

Saints Prokopiy & Ioann of Ustyug

Circa 1680

Egg tempera on wood panel

12.5” x 10.25”

James and Tatiana Jackson Collection

Saints Prokopiy and Ioann of Ustyug were given the distinction “Holy Fools.” In icons, holy fools were depicted either with very simple clothing, or no clothing at all. The holy fools of Russia abandoned possessions, even the appearance of intelligence,

|